AusWeb: What Did We Say? A Qualitative Data Analysis of the

Papers

J. Dale Burnett

dale.burnett@uleth.ca

University of Lethbridge

and

Allan Ellis

aellis@scu.edu.au

Southern Cross University

Abstract

Qualitative data analysis techniques were applied to the papers from four

AusWeb conferences in the period 1995 to 2001 to provide a metadata description

of the themes and topics. Comparisons among the descriptions for the four

conferences were then made in a search for commonalties and trends. Using

the four major categories of Education, Technical, Business and Society, a

number of patterns were identified. Education papers showed a shift away from

building operational Web sites to a concern for pedagogical principles that

take into account the technological character of the Web. Design, collaboration

and a concern for the learning process became increasingly mentioned. Technical

papers maintained a focus on integrating database technologies with the Web,

interest shifting from cgi-scripts to client-side approaches as well as to

new software developments such as DHTML and XML. Business papers, as might

be expected, focused on e-commerce but with a continuing interest in small

business environments. Society papers have predictably discussed social issues

such as equity, gender bias, government control, privacy and security.

1. Introduction

This paper addresses two questions: (1) can Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA)

software be utilized to provide a relatively quick description of several

sets of conference proceedings and (2) can such an analysis identify key issues,

trends and patterns?

The strategy was to first examine the most recent conference, AusWeb01, to

see if a qualitative data analysis would yield a useful, empirically grounded,

description. This being the case, we then reviewed the papers from the first

conference, AusWeb95. This was followed by squeezing in from both ends, looking

at AusWeb2K and AusWeb96, in order to make more substantive statements about

the differences in the descriptions and to comment on possible trends over

the years 1995 to 2001.

The authors would like to note that there is much more to a conference than

just the papers: keynote sessions, tutorials and workshops, panel discussions,

poster presentations and the opportunity to network informally on either a

one-to-one or small group basis. All of these components contribute to a successful

conference experience. It is also worth noting that the format for the presentation

of papers at AusWeb has always been nontraditional. Papers were placed on

the Web a month before each conference to allow delegates to read and perhaps

make preliminary decisions about which sessions they might attend. At the

conference, presenters were restricted to 5 - 10 minutes overview/updates

with the bulk of the time then being made available for questions and discussion.

Where possible 3 or 4 papers were grouped by a common theme so that in effect

each session had elements of a mini-panel format. The focus of each session

was therefore to allow delegates the opportunity to discuss and question the

authors rather than have authors give a presentation directed at the delegates.

2. Background of Qualitative Data Analysis

Denzin and Lincoln (2000) have provided one of the latest comprehensive handbooks

on qualitative data analysis. It is over a thousand pages in length and contains

a total of 41 chapters on specific topics by professionals recognized in their

field as being authorities on the selected topic. Ryan and Bernard (2000)

and Silverman (2000) as well as earlier books such as Miles and Huberman (1994)

and Dey (1993) provide excellent descriptions of the steps involved in conducting

a qualitative data analysis, beginning with the raw text, and proceeding through

an iterative series of steps of coding, revising, forming categories and hierarchies,

and finally arriving at either a complete description or a conceptual model

of the meanings inherent in the text. Strauss and Corbin (1990) provide an

excellent description of grounded theory approaches. In order to reduce the

considerable labor involved in this process a number of software packages

have been developed (Weitzman, 2000). In the present case, a package called

MAXQDA (earlier versions were called WinMAX) (Kuckartz, 2001) [HREF1],

currently available only for the PC, was used to aid in the coding and reorganization

of the data. Hall and Ellis (1998) [HREF2]

have conducted a similar analysis of data from messages appearing on a listserv

discussion board, wwwdev, using a program called NUD*IST (Qualitative Solutions

and Research Pty Ltd., 1994) [HREF3].

Usually QDA approaches are applied to interview data where the researcher

is attempting to determine the underlying ideas and assumption of the discourse.

There may only be a few inteviews, although these can be quite lengthy. The

present situation is almost the opposite, with the data consisting of titles,

keywords and abstracts of a large number of papers. However in both of these

cases the approach taken is one that is described in the literature as "grounded".

One begins with the data, in our case text taken from the conference proceedings,

and creates a series of codes that in some sense capture the main ideas of

the papers. The goal is to provide an empirically grounded description of

the papers presented at each conference and to then make comparisons among

these descriptions. The next four major sections provide descriptions, based

on a qualitative data analysis, of the four conferences AusWeb95, AusWeb 96,

AusWeb2K and AusWeb01. Details for the first analysis are provided in greater

detail in order to give a sense of the form of the QDA.

3. AusWeb01

AusWeb01 took place in April 2001 in Coffs Harbour, New South Wales. A total

of 26 refereed papers were presented.

3.1 Analysis of Paper Titles for AusWeb01

Let's begin with a description of exactly what is involved in coding just

the titles of the papers. The title of the first paper is "Inter-Study

Comparisons of Small Business Internet Use in Australia and New Zealand".

Should the word "Inter-Study" be a code? What about "Comparisons"?

Or should there be one code, "meta-analysis" to cover both of these

words? We might combine these alternatives by creating a code called meta-analysis

and then have the other two codes as sub-codes of this. Then we consider the

phrase "Small Business". This looks to be the main topic of the

paper. How important is the adjective "small"? Should I adopt the

previous strategy and create a code called Business and then create Small

Business as a sub-code, or should I simply code this as Business? The phrase

"Internet Use" can likely be ignored, since all papers at the conference

are likely to be about the Internet. Finally, are the names of Australia and

New Zealand significant? Should they be included as codes? What has just been

described is illustrative of a "ground-up" approach to QDA. One

begins with the data, in this case the titles of the papers, and tries to

create a set of codes that captures the words in the titles. As one can readily

see, this might entail a fair amount of careful work with the time taken to

be out of proportion to the possible benefits of the analysis. If nothing

else, at least this description may engender some respect, and sympathy, for

those who engage in this type of research. We will return to this when we

consider the keywords for each article.

A second approach is to begin with a small number of pre-established categories,

for example, the four tracks used in previous conferences, and add to them

if necessary as one reviews the papers. In this case the analysis is relatively

coarse-grained. Since the titles are often not sufficiently informative, it

is an easy matter to also scan the abstracts to obtain a better sense of the

paper. Thus the first paper might be categorized as "Business".

Continuing this approach yields the breakdown shown in Figure 1.

|

Category

|

Paper ID

|

| Education |

2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 |

| Business |

1, 9, 19, 26 |

| Technical |

5, 16 |

| Society |

10 |

Figure 1 AusWeb01 categories for refereed papers, N = 26

It turned out, at least for this analysis, that the defining criteria was

the environment within which the activity was located, rather than the type

of activity. It is not too difficult to revisit the articles and code the

papers to provide this additional information. The approach is still basically

grounded, with the codes being created as one proceeds through the papers.

The large number of papers in Education is the result of the granularity of

the earlier analysis and is an incentive to look for codes that are more informative

and which provide a clearer description of the content of the papers.

Each paper was assigned a single code based on the content of the title and

abstract. The resulting nine codes for Education are shown in Figure 2.

|

Codes

|

Paper ID

|

| online courses |

7, 8, 13, 21, 23 |

| administration |

11, 17, 18 |

| information retrieval |

2, 15, 25 |

| portals |

3, 4, 22 |

| authoring |

24 |

| community |

12 |

| research |

6 |

| simulation |

14 |

| staff development |

20 |

Figure 2 AusWeb01 codes for Education papers N = 19

3.2 Analysis of Keywords for AusWeb01

Authors were asked to supply a list of keywords to accompany their paper.

Such a list has two main uses. It presumably allows a potential reader to

use some form of search capability to see if a collection of papers contains

any matches to a list of keywords supplied by the reader, a match indicating

that the paper might be of related interest to the reader. This is basically

an algorithmic procedure and usually requires a "perfect match"

between a word or phrase supplied by the reader and the words or phrases supplied

by the author. Often a difference as small as an upper case letter, the difference

between a singular and plural form of the word, or the use/absence of a hyphen

are enough to prevent a match being detected.

There are three main ways to create a set of keywords for an article. The

first, easiest, and most common is to ask the authors to supply the keywords.

This had the additional advantage of leaving control in the hands of the author

who presumably is in the best position to know what the article is about.

The main weakness of this approach is the lack of any concordance or even

soft standard as to what criteria should be followed in making the list of

keywords. As a result there is the potential for a wide range of approaches

and resulting lists of keywords. A second way to create the list is to have

someone or some small committee review all of the papers and make the list.

This has, at least on the surface, the appearance of a common frame of reference

and standard, but it has the major weakness of perhaps missing the essential

idea or points of the article. It can also be quite time consuming for the

conference organizers. A third approach is to use a software program to automatically

scan the article and select out the keywords. It is an idea that may have

merit in principle, but the field of semantic analysis even leaves that as

an open question. At the moment the question of using keywords comes down

to a decision between asking the authors to supply such a list or to ignore

the idea completely.

The analysis of the keywords for each article began with a strict observance

of exactly what was supplied by the authors. In this case Figure 3 provides

a summary of the exact keywords for the total of 26 papers (2 papers failed

to supply keywords).

|

Keywords in the AusWeb01 papers

|

Frequency

|

| World Wide Web |

7

|

| Online Education |

6

|

| portal, E-business |

4

|

| Portals, personalization, customization, Management |

3

|

| 26 different words or phrases |

2

|

| 117 different words or phrases |

1

|

Figure 3 AusWeb01 frequency of keywords in titles of refereed

papers, N = 24

Using the algorithmic criteria of a "perfect match" it appears

that these papers have almost nothing in common. For a particular search using

any of the 143 words in the bottom two rows would yield only 1 or 2 hits.

This illustrates the weakness of using a search engine to search keywords

since the likelihood of a match for any particular keyword is remote. This

point is well understood by librarians, information retrieval officers and

engineers such as Tim Berners-Lee:

"The usual problem with keywords," Tim pointed out, "is

that two people never choose the same keywords." And while people may

recognize similarities in meaning between words, computers do not. (Gillies

& Cailliau, p. 183)

The other possible use of the keywords is more personal and heuristic: a

potential reader will scan the list and form a preliminary judgment that the

article is of interest. Even here, that is a questionable assumption. Most

readers are likely to do a very rapid scan of the entire article and then

form a judgment about its' potential value. However let's see what happens

when we begin to adjust the keywords to take into account minor differences

in spelling. As a start we can delete the keywords World Wide Web or WWW or

Web since it may be safely assumed that all papers are on that topic.

If you have engaged in QDA you realize that it can

quickly become very complex. There is a high level of judgment involved in

determining the meaning of a particular code, and in deciding whether a particular

code should, or should not, be considered a sub-code of another code. Other

issues related to synonyms, and to context, can become difficult. Even authors

who may not be interested in qualitative approaches may be sensitive to some

of the problems. For example, the supplied keywords for one paper included

the following: "Electronic commerce, e-commerce, eCommerce, electronic

business, e-business, eBusiness, electronic marketing, e-marketing, eMarketing,

online marketing, small business, Internet commerce, World Wide Web, Web".

At the other end of some imaginary continuum was a paper with the following

list: "BURKS, CD-ROM, educational software".

A decision was made to drop the analysis of keywords from the remainder of

the study. It might even be suggested that this component be dropped from

paper submissions to the conferences, and perhaps the idea might be extended

to professional journals as well. The original intent would appear to have

merit, but it does not appear to bear up well under scrutiny.

3.3 Analysis of the Abstracts for AusWeb01

Given the generally efficient method of forming categories when looking at

the titles, but which often involved a reading of the Abstracts as well, and

given the difficulties encountered when attempting a coding using the supplied

keywords, it was reasonable to doubt that much additional value would accrue

from a detailed coding of the abstracts. One advantage with this attempt was

that the researcher had control over the codes and could thus restrict the

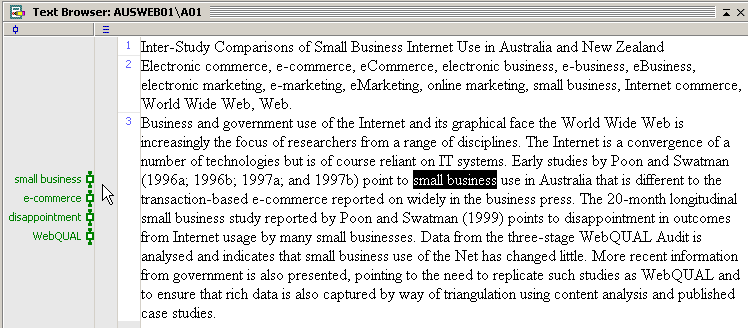

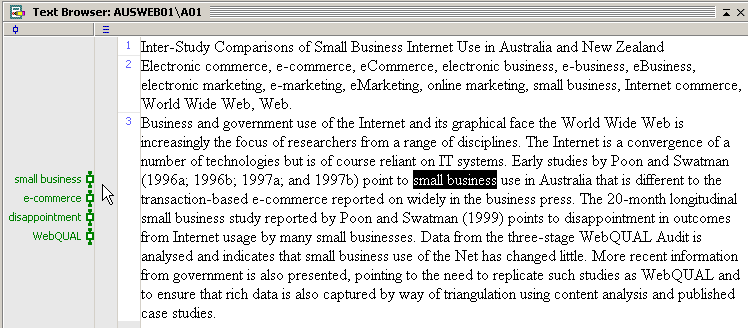

proliferation of synonyms. Figure 4 is a partial screen capture from the program

MAXQDA showing the codes that have been inserted for the first abstract. The

codes are in the left margin (in green). Clicking on a code highlights the

text in the document that received that code. This allows one to distinguish

between codes that appear as a direct copy of the author's vocabulary as compared

with a code that might be a paraphrase created by the researcher. The clear

majority of codes in this study were direct quotes.

Figure 4 Screen display of coding process showing highlighted

text and in the left column the code name and code marker

One can then obtain a list of frequencies for any group of selected

papers. For example, Figure 5 gives the frequencies of codes for the four

business papers identified in Figure 1.

|

Frequency

|

Code

|

|

3

|

e-commerce |

|

2

|

small business |

|

1

|

bandwidth, current usage, disappointment, globalization,

governance, income, intended use, isolated organizations, mobile agents,

reliable, security issues, taxation, underlying knowledge, WebQUAL |

Figure 5 AusWeb01 display of frequency and codes for Business

papers

A scan of this list is more informative than the simple categorization

of the papers as being about Business. This suggests that the effort involved

in coding the abstracts for the papers for Education might in fact be worthwhile.

Figure 6 shows the most frequent codes for the 19 Education

papers.

|

Frequency

|

Code

|

|

8

|

Online Education |

|

6

|

post-secondary/higher education |

|

4

|

portal |

|

3

|

customization, personalization, Web-based instruction |

|

2

|

flexible delivery, infrastructure, interoperability, management,

metadata, subject gateway, survey, university, |

|

1

|

68 individual codes |

Figure 6 AusWeb01 display of frequency and codes for 19 Education

papers

The codes give an improved sense of the content of these papers.

While variety is the norm, particularly with the codes occurring only once,

one nonetheless has a clearer sense of the nature of that variety.

It is also possible to construct a more fine grained analysis.

For example, Figure 7 shows the codes in papers about online courses. These

codes had the same structure, namely very little overlap of codes and an increasingly

long list of unique identifiers. Further analysis placed these 54 codes into

3 categories: Course Design, Course Evaluation and Staff Issues, which gave

a clearer picture of the topics mentioned in these seven papers.

|

Category

|

Codes

|

| Course Design |

language learning, document creation, delivery model,multimedia, offline

use, distance education, disadvantages, Hybrid Delivery System, combination

of online and traditional methods, computer literacy skills, interactivity,

personalization, customization, audio visual interactive, courseware management,

CD-ROM |

| Course Evaluation |

remote campuses, Computer Science students, network bandwidth, increased

flexibility, evaluation, viewed online favorably, lack of resources, eleven

recommendations, lack of immediacy in feedback, difficulties, perceptions

of students |

| Staff Issues |

amount of traditional teaching, Faculty of Applied Science, goals and

plans, actual implementation steps, practical support, principles for

guiding on-line development, large number of projects, funding, technological

barriers, little involvement in on-line delivery, doubts about benefits

for students, doubts about on-line pedagogy, mistrust of institutional

motivation, enthusiastic early adopters, leadership and mentoring, Web-based

presence for all courses, empowering of staff, staff development |

Figure 7 AusWeb01 categorization of codes in papers on "Online

Courses"

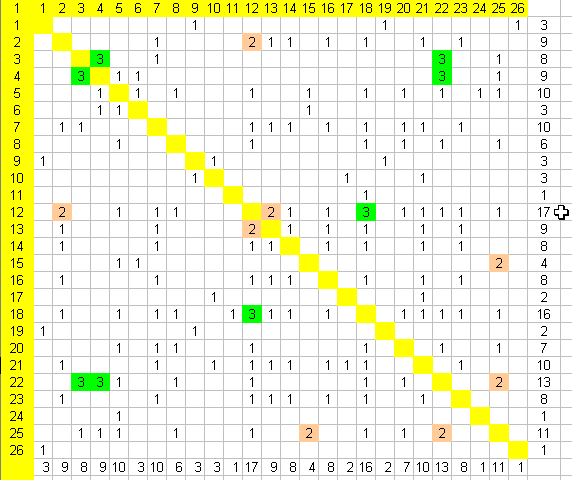

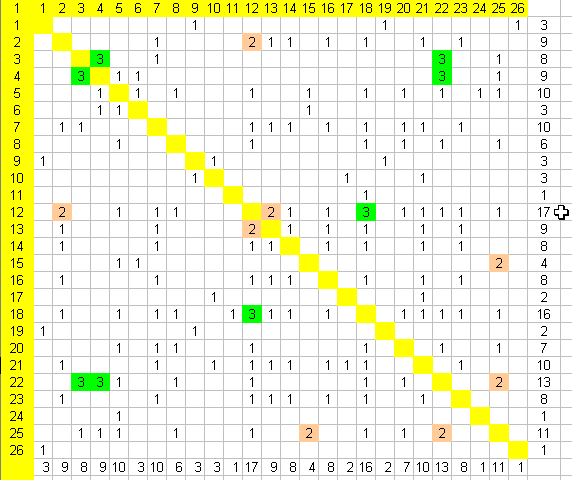

In addition to the above summary, the codes from the QDA permit a more detailed examination of the similarities among

the 26 papers. For example, it is not that difficult to construct a matrix

where the rows and columns are the paper IDs, and the number in the cell where

a row and column intersect provides the frequency of the number of nodes that

the two papers have in common. In the present case this matrix looks like

this:

Figure 8 Similarity matrix showing the number of codes that

any two AusWeb01 papers have in common

The numbers identifying the rows and columns refer to the number

of the refereed paper. The cells highlighted in dark grey (green on screen)

indicate the papers that have 3 codes in common. For example, papers 12 and

18 have the codes "Online Education", "Web-based instruction"

and "post-secondary/higher education" in common. The mid-grey (tan)

cells indicate papers that have two codes in common. Looking at the total

number of common codes for each paper, displayed as the rightmost column,

it also becomes apparent that paper 12 has the most codes (17) with the conference

as a whole. At the other end of the scale, papers 11, 24 and 26 are virtually

unique with only 1 code in common with another paper.

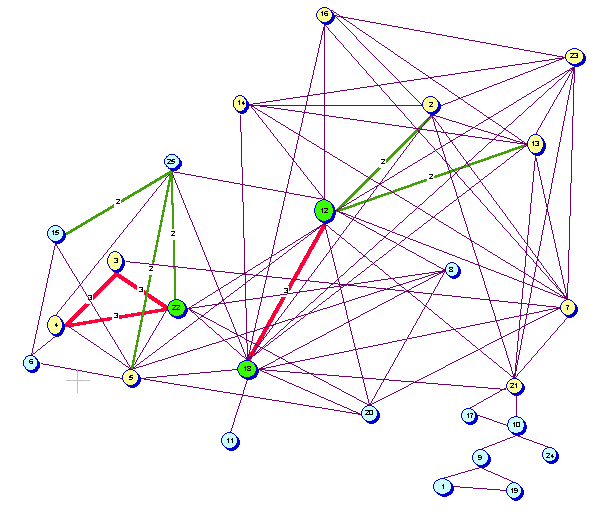

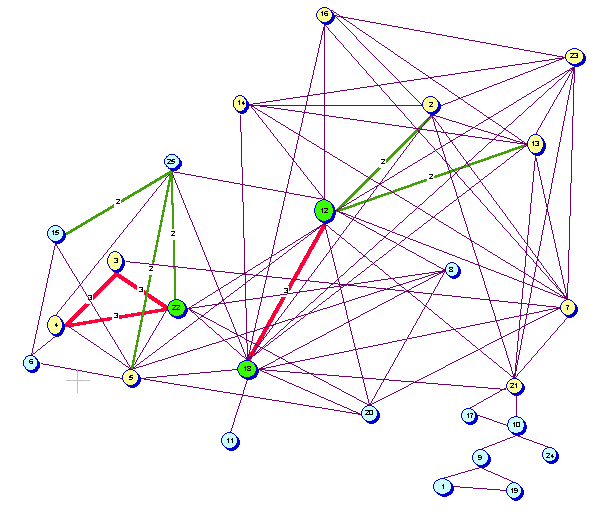

Figure 9 is a graphic image (generated by the software package

Inspiration [HREF4]) for this situation

for the 26 papers. In this case each paper (the numbered circles) has a line

corresponding to the commonality of codes with the other papers. The additional

numbers on some of the lines indicates the number of codes that two papers

have in common. These lines are also thicker and on the screen display, are

in color (red for 3 common codes, green for 2 common codes). The overall pattern

shows a visual representation of the interconnectedness among the papers.

Figure 9 Connections among the AusWeb01 papers based on common

codes

Another way to organize this information is by the frequency

of codes. This provides a useful index if one is interested in noting whether

a particular topic is discussed in the collection of papers.

|

Code

|

Paper ID

|

| online education |

2, 7, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 21, 23 |

| post-secondary/university |

5, 8, 12, 18, 20, 22, 25 |

| portal |

3, 4, 22, 25 |

|

customization

|

3, 4, 22 |

| e-commerce |

1, 9, 19 |

| infrastructure |

4, 5, 6 |

| management |

10, 17, 21 |

| personalization |

3, 4, 22 |

| Web-based instruction |

12, 13, 18 |

|

design

|

5, 24 |

|

flexible delivery

|

11, 18 |

|

governance

|

9, 10 |

|

interactive learning

|

7, 20 |

|

interoperability

|

6, 15 |

|

learning environment

|

5, 15 |

|

metadata

|

15, 25 |

|

small business

|

1, 26 |

|

subject gateway

|

15, 25 |

|

survey

|

3, 7 |

Figure 10 Frequency of codes in AusWeb01 papers

However it is worth noting that these displays are nowhere near as useful

as the actual dynamic use of the MAXQDA software, where one can not only see

which papers may have a common topic but that with a mouse click you can go

directly to that particular section of the appropriate document. This is the

real strength of software developed for QDA and is the reward for the hours

spent coding the raw data.

4. AusWeb95

As is often the case with empirical research, the expectations of the researchers

may be at variance with the reality being examined. It turns out that the

format for papers in 1995, the first conference, did not include abstracts.

After a bit of thought, and a check to see if it was feasible, it was decided

to extract the introductory and concluding sections of each paper and treat

that as a (slightly larger!) abstract. This appeared to work reasonably well

and a resulting text file of about 60 pages was assembled. A total of 60 refereed

papers was used in this analysis. Having discarded the idea of further analysis

of the keywords, the analysis focused on a combination of title and extracts

as the textual database for a QDA.

The conference was organized into sessions with the following titles (the

numbers refer to the session ID used in the conference):

1. Education (with a Science flavour)

2. Libraries

3. Education (with a flavour of application to learning)

4. Hypertext theory, interfaces, presentation standards

5. Education

7. Education

8. Web tools

9. Management Tools

10. The Web Future & Commerce on the Web

11. Publishing on the Web

12. Indexing, caching, robots, spiders

13. Collaborative use of the Web, sociology of the Web

15. Connectivity and emerging services

16. Integrating external applications

(Note: sessions 6 and 14 were non-paper sessions)

These 14 sessions were reorganized into the 4 tracks (or categories) used

for the conference.

|

Category

|

Track ID

|

No. of Papers

|

| Education |

1, 3, 5, 7 |

18

|

| Business |

10 |

5

|

| Technical |

4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 16 |

23

|

| Society |

2, 11, 13 |

14

|

Figure 11 Categories for all refereed papers in AusWeb95

Two types of subsequent analysis were performed: one on each of these categories,

the other on the combined total of 60 papers.

Let's examine the categories first, before combining the data. For Education,

a total of 18 papers were coded. The coding was restricted to one occurrence

of the code for each article. Thus the numbers correspond to the number

of papers that had that code.

Figure 12 Partial screen capture showing code names and

frequency for Education papers in AusWeb95

Another 14 codes occurred in 1 article each, for a total of 42 descriptors.

Figure 13 gives a sense of the topics that were important to the Education

track in 1995.

|

Category

|

Codes

|

freq. |

| Web support for Courses |

learning aid, courseware, designing Web pages, online testing, pedagogical

principles, self-paced learning, Web authoring - HTML, computer managed

learning environment, mixed Internet-CDROM delivery, simulation, |

10 |

| Implementation |

access, initial effort, costs, distance education, copyright, index,

planning, school education, |

8 |

| Technology |

interactive interface, multimedia, email, forms, newsgroups, hypermedia,

slow access, ftp, gopher - WAIS, pdf, problems with browsers |

11 |

| Implications |

need for training, research, changing role of instructor, collegial

communication, community, search strategies, communication, collaborative

learning, equity, peer review of courses, censorship, security, student

publishing |

13 |

Figure 13 Categorization of codes in papers on Education

in AusWeb95

The above analyses are intended to show the level of detail that a grounded

QDA description can provide. Although it is possible to continue providing

this level of analysis and description for AusWeb2K and AusWeb96, the primary

purpose was to compare the results of such an analysis for all four conferences

that span the time from 1995 to 2001.

5. Combined Analysis for the Codes for AusWeb95, 96, 2K, 01 Conferences

To facilitate comparisons, a separate table (Figure 14) was constructed showing

the number of papers for each of the four categories.

| Category |

AusWeb95

|

AusWeb96

|

AusWeb2K

|

AusWeb01

|

Total

|

| Education |

18

|

25

|

14

|

19

|

76

|

| Technical |

23

|

18

|

13

|

2

|

56

|

| Business |

5

|

8

|

5

|

4

|

22

|

| Society |

14

|

7

|

0

|

1

|

22

|

|

Total No. of Papers

|

60

|

58

|

32

|

26

|

176

|

Figure 14 Categorical distribution of refereed papers for

all 4 AusWeb conferences

Finally, each of these four categories was organized by the

successive AusWeb conferences and a list of the codes used within each category

was displayed by the relative frequency of its occurrence. Figures 15 to 18

provide a comprehensive summary of the codes utilized by the authors of these

176 papers.

|

Category

|

Codes

|

|

Education

|

| AusWeb95 |

[13 times] learning aid

[9 times] access, initial effort

[6 times] multimedia

[5 times] changing role of instructor, community, interactive

interface, need for training, research

[4 times] collegial communication, costs, courseware, designing

Web pages, distance education, email, online testing, pedagogical

principles, search strategies

[3 times] communication, forms, newsgroups.

[2 times] collaborative learning, equity, gopher and WAIS, hypermedia,

peer review of courses, self-paced learning, slow access, Web

authoring.

[1 time] administration, censorship, computer managed learning

environment, copyright, ftp, index, mixed internet/CD-ROM delivery,

pdf, planning, problems with browsers, security, simulation, student

publishing.

|

| AusWeb96 |

[5 times] collaborative teaching and learning.

[4 times] online support for courses.

[3 times] CGI, distance education, electronic journal, instructor

acceptance, managing courses, staff development.

[2 times] courseware, email, hypertext, K-12, multimedia, navigation,

privacy, security, Web server.

[1 time] alliance networks, annotations, career option, cost,

experiential model of learning, indexing tools, interactive Web

pages, learner control, mailing lists, modular, narrative, online

testing and grades, pedagogy, prepublication, reflection, research,

self-paced learning, social/political, student perceptions, WAIS

and gopher, Web authoring Web forms.

|

| AusWeb2K |

[3 times] pedagogy, Web searching.

[2 times] collaborative learning process, e-mail, evaluation,

metadata, staff development, students, Web-based course design,

Web-based learning, XML.

[1 time] attitudes, cultural background, knowledge management,

multimedia, on-line communities, public access, security, subject

gateways, teaching and learning center, W3C, Web-based assessment,

Web page collaboration tools, Web teams.

|

| AusWeb01 |

[4 times] portal.

[3 times] Web-based instruction, personalisation, customisation.

[2 times] survey, subject gateway, metadata, management, interoperability,

infrastructure, flexible delivery, situated learning, staff development.

[1 time] authentic activities, authoring, AVEL, Bioinformatics,

BURKS, CALL, CD-ROM, census, change management, classroom, cognitive

apprenticeship, collaborative learning, community, computer literacy,

computer mediated communication, conceptual tool, copyright, CORBA,

costs, customer service, deconstructing, design,distributed computing,

educational software, enculturation, hyperspace, information access,

information management, integration, intellectual property, interactive

environment, interactive learning, metaphor, multimedia, online

courseware development, online registration, ownership, self-study,

sense-making, simulation, situated learning, staff development,

technical support, Web-based course management system, XML.

|

|

Figure 15 Codes used by Education refereed papers

|

Category

|

Codes

|

|

Technical

|

| AusWeb95 |

[11 times] databases

[7 times] access, designing Web pages, search strategies.

[5 times] costs, email, multimedia.

[4 times] cgi, community, forms, hypermedia, index, Web server.

[3 times] communication, ftp, initial effort, research, security.

[2 times] administration, authority, bandwidth, common client

interface, gopher & WAIS, government information, navigation,

provide information about organization, slow access, Web authoring.

[1 time] collaborative research, concept map, copyright, course

materials, courseware, empower, image compression, interactive

interface, library, need for training, newsgroups, planning, video

conferencing, work at home.

|

| AusWeb96 |

[4 times] hypertext

[3 times] multimedia, navigation, Web server.

[2 times] CD-ROM, intranet, search tools, security.

[1 time] adaptive systems, ATM, Bifocal display, e-commerce, email,

hard-copy printing, ISDN, Java, Legacy, modular, notebook computer,

PGP, public domain, search agent, shareware, software robots, Spider,

user authentication, Web authoring, Web browsers, wide area network. |

| AusWeb2K |

[3 times] evaluation

[2 times] electronic profiling, navigation, privacy, usability,

Web page collaboration tools.

[1 time] automated analysis, client-side scripting, collaboration,

collection, commercial data collections, contextual information,

data-centric approach, database, design, DHTML, e-commerce, hierarchically

organized, legal position, multifaceted approach, multimedia,

online marketing research, personal information, project management,

scale up, search engines, site management, students, thematic-based

collection, upgrading, Web searching, Web server, Web teams, XML,

XQL, XSL.

|

| AusWeb01 |

[1 time] design, development, forum software, forums, hybrid delivery

system, HyWeb, implementation, infrastructure, learning environment,

online, online education, post-secondary/higher education, university,

WBI. |

|

Figure 16 Codes used by Technical refereed papers

|

Category

|

Codes

|

|

Business

|

| AusWeb95 |

[3 times] communication.

[2 times] costs

[1 time] administration, collaborative research, community, copyright,

databases, email, government information, initial effort, planning,

social movements, video conferencing, work at home. |

| AusWeb96 |

[5 times] e-commerce

[4 times] intranet

[2 times] database, marketing, small companies

[1 time] cost, email, entrepreneurship, ISP, large companies, research,

security. |

| AusWeb2K |

[3 times] e-commerce.

[2 times] marketing, online business models, portal.

[1 time] barriers to e-commerce adoption, diffusion models, economic

development, online marketing research, productivity increases,

residential real estate market, service augmentation, social development,

trade hubs.

|

| AusWeb01 |

[3 times] e-commerce.

[2 times] small business.

[1 time] bandwidth, current usage, disappointment, globalisation,

governance, income, intended use, isolated organizations, mobile

agents, reliable, security issues, taxation, underlying knowledge,

WebQUAL.

|

|

Figure 17 Codes used by Business refereed papers

|

Category

|

Codes

|

|

Society

|

| AusWeb95 |

[7 times] access

[6 times] research

[5 times] collaborative research, communication, electronic publishing

[4 times] costs, databases, library, search strategies.

[3 times] community, gopher & WAIS, hypermedia.

[2 times] changing role of librarian, collegial communication,

designing Web pages, email, forms, ftp, initial effort.

[1 time] bandwidth, cgi, ease of use, electronic journal, empower,

equity, gender, government information, identity, index, listservers,

multimedia, need for training, planning, rapid change, refereeing

process, slow access, social interaction, Web server, work at

home.

|

| AusWeb96 |

[2 times] censorship, copyright

[1 time] archives, collaboration, community, cost, feminist deconstruction,

free public access, gender bias, intranet, legislative measures,

marketing, policy, research, security. |

| AusWeb2K |

none

|

| AusWeb01 |

[1 time] content, control, filtering, gambling, governance, IP

blocking, management, monitoring, moratorium, prevention. |

|

Figure 18 Codes used by Society refereed papers

All four tables are both rich and suggestive as well as to some

extent fragile. Rather than attempt to state a definitive set of conclusions

we would like to suggest of couple of possible interpretations. This leaves

the way open for delegates and other readers to draw their own additional

conclusions.

Education papers showed a shift away from building operational

Web sites to a concern for pedagogical principles that take into account the

technological character of the Web. Collaborative learning was a common theme

in all four conferences whereas design and a concern for the learning process

became mentioned increasingly often. Technical papers maintained a focus on

integrating database technology with the Web, interest shifting from cgi-scripts

to client-side approaches. The evolution of markup languages from HTML to

DHTML and XML is also reflected in the papers. Not surprisingly, papers in

the Business category centered on e-commerce with a discernible continuing

interest in small business environments. Recent business papers show evidence

of more pragmatism and even disappointment with some of models. The final

group of papers, loosely identified as "Society" are more idiosyncratic

and show a sensitivity to a wide range of social issues such as government

control, privacy, security, gender bias and equity.

6. Demographic Analyses Across AusWeb95, 96, 2K and 01

Three tables (Figures 19, 20, 21) were created that provide information on

gender, geography and broad category of topic. The gender distribution (Figure

19) of the presenters was computed based on the approximately 80% of the names

that had a popular gender connotation. The ratios are strikingly consistent

across the four conferences.

| Conference |

M (%)

|

F (%)

|

| AusWeb95 |

75

|

25

|

| AusWeb96 |

68

|

32

|

| AusWeb2K |

65

|

35

|

| AusWeb01 |

67

|

33

|

Figure 19 Gender distribution of presenters for all 4 AusWeb

conferences

Information about the geographic location of the presenters was collated

for each conference (Figure 20). Once again, the frequencies are quite stable.

|

Location

|

AusWeb95

|

AusWeb96

|

AusWeb2K

|

AusWeb01

|

Total

|

| Victoria |

21

|

9

|

12

|

10

|

52

|

| New South Wales/ACT |

17

|

19

|

8

|

5

|

49

|

| Queensland |

7

|

13

|

5

|

6

|

31

|

| West Australia |

5

|

6

|

1

|

1

|

13

|

| South Australia |

2

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

5

|

| Tasmania |

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

| International |

7

|

10

|

5

|

5

|

27

|

| Totals |

60

|

60

|

32

|

28

|

180

|

Figure 20 Geographical distribution of authors for all 4

AusWeb conferences

This shows a strong representation from Victoria, New South Wales/ACT and

Queensland. The most obvious interpretation of this pattern is the east

coast venues for the conferences. Numbers from other states were appreciably

less, falling to no representation from some states in some years. The international

presenters came from Belgium, Canada, England, Greece, Hong Kong, Ireland,

Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland and the United States.

It is worth noting that each conference had a contingent of international

presenters.

8. Summary and Comments

What did we say? The fine grained analysis (Figures 15 to 18) shows the diversity

of topics addressed by presenters at the conference. When looked at across

the years, Education and Business showed a fairly level pattern of contribution.

The Technical area had a contribution level similar to Education in all except

the last year. Society showing a marked decrease between the first two years

and the last two years.

This analysis has demonstrated that a grounded QDA of just the titles and

abstracts can be used to provide a fine-grained description of the content

of papers presented at a conference. The approach was also able to identify

many of the specific topics and issues within papers as well as links among

papers. The tables providing a detailed list of the coding for the papers

may give rise to a new set of investigations from readers whose interest had

been stimulated by a perceived trend or piqued by a particular word or phrase.

The results may also provide future conference organizers with a basis for

designing a call for papers that builds on areas of increasing popularity,

or conversely, suggests topics that appear to be waning.

This paper has demonstrated an application of QDA to a topic not normally

subject to such analysis. The ideas and issues underlying QDA are also central

to those that will support the development of a theme that will almost certainly

be of major interest at future AusWeb conferences - the Semantic Web.

References

Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.) (2000). Handbook of qualitative research.

2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dey, I. (1993). Qualitative data analysis: A user-friendly guide for social

scientists. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Gillies, J. & Cailliau, R. (2000). How the Web was born. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Hall, R. & Ellis, A. (October, 1998). What do Web-based courseware developers

discuss? A qualitative analysis of the WWWdev Listserv. Proceedings of the North

American Web Developers Conference, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada.

Kuckartz, U. (2001). MAX Qualitative Data Analysis Introduction. VERBI Software.

Berlin: Germany.

Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded

sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Qualitative Solutions and Research Pty Ltd. (1994). Q.S.R. NUD*IST Revision

3.0. User Guide. Melbourne, Australia: Qualitative Solutions and Research Pty

Ltd.

Ryan, G. W. & Bernard, H. R. (2000). Data management and analysis methods.

In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.) Handbook of Qualitative Research.

2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 769 - 802.

Silverman, D. (2000). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. London:

Sage Publications.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded

theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Weitzman, E. A. (2000). Software and qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin

& Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.) Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 803 - 820.

Hypertext References

HREF1

http://www.maxqda.com

HREF2

http://naweb.unb.ca/proceedings/1998/hall/hall.html

HREF3

http://www.qsr.com.au/

HREF4

http://www.inspiration.com/